The School that Disappeared

By Paul Croxson

It was a simple enough request, ‘What did I know about the Intelligence schools and their numbering?’ ‘Not a lot,’ was the answer. The title ‘schools’ seemed designed to confuse the enemy. Their primary function was to direct the search for specific German signals. Not much more than this was recorded.

To be honest, I hadn’t looked at this subject for a number of years during my Sigint searches and so just sent off some scrambled notes that I happened to have following some research for the late Alan Edwards. When I later read them, I realised that they were in somewhat of a mess and so spent some time sorting the various schools into some semblance of numerical order. All the schools of intelligence I had details of, seemed to be numbered. One thing was apparent though, I had not been able to trace where No. 1 Intelligence School was located and what went on there. I was well aware of the schools numbered 2 to 7 but no. 1 appeared to have evaded me. I decided to spend an hour or so trying to find the answer to the ‘missing’ School. I did find two un-numbered schools but these were cipher schools, one in Herne Hill, SE London and the other in Yorkshire. Not what I was looking for; they were mainly Royal Signals training establishments, it seemed!

In my search for clues, I found myself, once again, buried in what I consider to be possibly one of the best-informed books on Enigma, The Hut Six Story written by Gordon Welchman, one of the foremost members of B.P and certainly without the approval of the authorities. In passing. I find it quite extraordinary that so much credit is given to Alan Turing for the breaking of Enigma and the development of the Bombes, whilst the major contribution made by Gordon Welchman is virtually ignored. In my view, which is now becoming the accepted view, Welchman’s contribution to the solving of Enigma and the creation and development of the system of Huts 3, 6 and 8 was of paramount importance: equalling Turing. One might say that he ‘industrialised the extraction of Enigma intelligence’. In addition, it is impossible to put a value on his immense contribution to the development of the Bombe which resulted in there being some disagreement between him and Turing – which is, again, often glossed over. The Bombes would have been much weaker unless or until someone else had his flash of inspiration about the diagonal board turning them into potent indispensable weapons in the fight against Enigma.

As Peter Calvocoressi, who also worked at B.P, pointed out, in its pre-war incarnation the Government Code & Cipher School under the Foreign Office was exactly what its name implied and no more. ‘Intelligence’ played a very small part, it being left to SIS, their neighbours in London. Welchman’s great contribution was to ‘marry a scarcely formed intelligence process to code breaking, forming a sophisticated system for Sigint exploitation’, which in parallel with Winterbotham’s contribution enabled the safe dissemination of the ‘product’, worldwide to all three Services and the SIS.

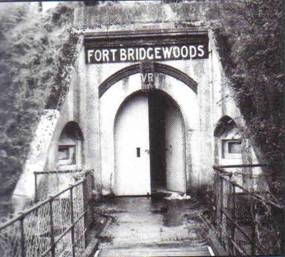

The three armed services had each built up their own intercept networks; some, as early as the twenties, but separate and more secret still were those operated by the Foreign Office, MI5 and MI6 who were listening to the highest levels of German Secret Service communications. Fort Bridgewoods near Chatham was one of these, with its civilian staff of operators.

When I first read Hut 6 some twenty-odd years ago I knew very little of the story of Bletchley Park and Enigma and so was delighted to be re-acquainted with the story, knowing, as I do, so much more now about what went on there; particularly reading his accounts, sadly not very lengthy or detailed, of the work carried out at Fort Bridgewoods. I had heard of its existence but little of its role in the development of interception. Welchman mentions it several times and praises it – in particular the commanding officer, Commander Ellingworth – as being an important tool in his search for the solution of Enigma. There are just tantalising glimpses. It was another piece that I could put in place in the puzzle.

The Fort played several vital roles in the Enigma story, not least in the training of civilian intercept officers who, as civilians would form the backbone of the intercept service in the UK. (Could this be then the missing No. 1 School)? These operators were of a standard unmatched anywhere at the time. Since accuracy – particularly when recording the preambles – was vital in the search for Enigma, their work was greatly prized. As the workload increased and they moved from Chatham, they would go on to train army personnel at both Chicksands and Beaumanor.

What again was interesting and worthy of further investigation was the battle for control of the intercept sets between Ellingwworth and Welchman and Colonel (Arcedekne) Butler, Head of MI8. MI8 had retained responsibility for what is often called the ‘steering’ of the intercept, despite efforts by the growing GC & CS to take it over. In correspondence from Welchman to Travis, the then Deputy Head at GC & CS he specifically refers to this problem, pointing out that ‘ his view there was no need for ‘another intelligence school’! (I had been diverted from my search for No. 1 Intelligence School but was this a clue to lead me back to the straight and narrow?) What new school been proposed and by whom?

Welchman had built up what was a very good and fruitful working relationship with Ellingworth and his intercept team. This, however, did not apply to Butler, the head of MI8: far from it! On 1 April 1941, Welchman wrote what is by any standards a highly critical and inflammatory letter to Commander E Travis, at the time deputy director of B.P. regarding the Head of MI8. He wrote,

Unfortunately, Col. Butler has continually tried to take away the work of the Chatham Intelligence School and to interfere with our (GC & CS) close co-operation with Cdr Ellingsworth. He has founded unnecessary organisations in London and elsewhere which he attempts to place between us and the (intercept) stations. We and Cdr Ellingsworth have had to waste a considerable amount of energy in fighting changes which we knew to be against the national interest. The latest danger lies in the formation of Intelligence School No, VI under a new colonel who knows nothing about ‘E’ traffic from the cryptological or from the wireless point of view. We are to be deprived of the greater part of the valuable intelligence work that has been done under Ellsworth and instead we are asked to accept

intelligence from another party whose reliability we do not trust’. . . ‘the clash is between Cdr Ellingsworth’s intelligence school (so, it was an Intelligence School at Chatham) and Col. Butler’s intelligence School. We say without hesitation that the former is essential to us chiefly owing to the experience of Cdr Ellingsworth himself and that Col. Butler’s school is not only unnecessary but a nuisance. The work that has been done by Col. Butler’s party could have been done better under Ellingsworth at GC & CS.

And this was at what was possibly one of the most dangerous periods in our history! This was extremely strong – almost venomous – criticism of the man who headed up MI8 and a serious comment on the units he was responsible for, not least 6 I.S., which went on to perform a vital role finally forming the backbone of what would become known as ‘SIXTA’ at B.P. At this point Welchman’s patience with Butler seems to be exhausted to the extent that his dissatisfaction was recorded in writing at the highest level! It is important to appreciate that these disputes were not always about the same problem which in retrospect is almost unbelievable at such a critical time in the war. Although he, Welchman, had clearly lost patience and trust with Arcedeckne-Butler he certainly was very much in favour of what could be achieved within his MI8 organisation.

Gordon Welchman undoubtedly was one of the greatest contributors to the success of ULTRA intelligence, having first established contact with it in December 1940. Farsightedly, he certainly saw the presence of the log-readers in the future lay at B.P. rather than Beaumanor or London as he made very clear in Hut Six.1 On 17 July 1941 6 I.S. moved from London to Beaumanor. Shortly after this, on June 16 1941, Colonel Arcedeckne-Butler left MI8 and was succeeded by Colonel Nicholls (later Brigadier F W Nicholls), Royal Signals. Although nothing is said in the records, no doubt there was probably an almost universal sigh of relief at his departure.

To make matters worse, there were still problems; the quarrels between GC & CS and MI8 which had precipitated the inquiry in the winter of 1940/1941 still had not died down despite the departure of Butler. These quarrels erupted again, mainly centred on the fact that, while MI8 was responsible for intercepting German Army and GAF traffic and for subjecting it to traffic analysis, GC & CS controlled Cryptanalysis separately and independently from intelligence. It was this dichotomy that would always be a cause for discussion and dissent, until resolved when it later became an accepted fact that cryptanalysis and traffic analysis are inseparable, or at least, not easily separated: but this was in the future.

Perhaps a potted history of the Fort would not go amiss. It was built in the late 19th century as one of the forts that defended the landward approach to Chatham Dockyard. It protected the approach from Maidstone and the flank of Fort Borstal. It was polygonal in shape and had a deep dry ditch around it. The entrance was via a roller bridge and either side of the entrance gate were machine

gun loops, which was the first appearance of this feature at Chatham. The fort was first started in about 1879 by convict labour, but due to lack of money and a fading enthusiasm for building forts, work stopped and it wasn’t until 1892 that Fort Bridgewoods was finally completed

A War Office Y (intercept) station had been based at Fort Bridgewoods since 1926, initially responsible to GC & CS and then, following its creation in 1938, to MI8. The first five operators not only carried out overseas interception work of which there was very little to do in those early days; but also other tasks; for example, in their very early days at one time they were even on loan to Chelsea Barracks where they provided point-to-point communications with other government stations around the country during the General Strike.

1 The Hut Six Story, W.G. Welchman, McGraw Hill, 1984

Although by then, nominally a Royal Signals establishment, from January 1935 the station was staffed by civilian operators commanded by Lieutenant Commander (retd) M J W Ellingworth RN, and responsible to GC & CS. The station was the first to regularly intercept German wireless traffic recognised as being sent in the high-grade Enigma cipher and was, for a time, the mainstay for providing intercepted wireless traffic for the few codebreakers who would eventually end up at Bletchley Park. By 1933/34 the Enigma machine had been adopted by the Germans as a basic unitary cipher system for the three armed forces, as well as military intelligence (the Abwehr), SS formations, Nazi Party security and political intelligence service (S.D.). Even other agencies of the Third Reich such as the railways and police eventually adopted it in various formats. What was key to the success of the Enigma machine was that, with minor modifications, Enigma could be used independently and in total safety by all of these organisations.

There was not that much traffic to intercept. From the outbreak of war until the invasion firstly of Norway and Denmark and then France, virtually complete radio silence was initially adopted by the Germans. Following the invasions with landlines not being initially available, German wireless activities greatly increased. A hutted encampment was built in the woods adjacent to the fort to house the increase in operators, and also other buildings were built inside the fort to house the teleprinter operators and other clerical staff.

It might seem an elementary question but how did the interceptors know that the messages that they were intercepting came from German sources and how did they recognise them as being Enigma? Direction finding had made the origin of the messages obvious very quickly. To cryptologists, an Enigma cipher was easily recognisable by its nearly perfect disposal of letters with the messages in neat five-letter groups. It didn’t correlate with natural language – in any language some letters occur more frequently than others – and statistical calculations of frequencies of the letters were completely useless. It had to be a machine cipher that was being used; something UK cryptologists had been fearing for some time.

Fortunately, most messages had two characteristics besides the wireless frequency in which they were being transmitted. As well as the geographical point of origin which could be established by direction finding they carried the callsign of the sender who would identify himself at the start of a message; the equivalent of starting with their name and address. By a combination of these it was possible to establish that a unit using such-and-such frequency was located at or near X. Even without reading the actual message there was intelligence to be gained. Military intelligence, under MI8 had worked for some time on the assumption that any machine-enciphered messages would be impossible to decrypt. This should have been the case!

Most of the British-intercepted Enigma messages which were being studied by GC & CS were being ‘plucked out of the ether’ by the then very experienced civilian operators at Chatham. Unbeknown to them, they were also being intercepted by both the Poles and the French. Each day’s accumulation of messages, painstakingly and accurately handwritten by the operators, was regularly bundled up and sent to B.P., together with a report on the day’s traffic. The operators were under the impression that the messages were being deciphered which accounted for the care with which they were recording them. Alex Kendrick, a civilian member of ‘Dilly’ Knox’s2 staff at B.P. had been given the task of indoctrinating Welchman on his arrival into the little that was known about Enigma. It was these reports, not the messages, that Gordon Welchman and Kendrick worked on at B.P. in the early days with very little guidance from Knox the nominal Head of the department. They concentrated on what were to be known as ‘callsigns and discriminants’, working at B.P. in what was then referred to as the ‘School’ based on it having been originally part of Elmers School. (No, this was not the missing No. 1 Intelligence School). In the early days there was little organisation and cooperation between the staff at B.P.; this level of work had never been envisaged. For example, in the early days when Welchman made what he thought was an important breakthrough, he rushed to tell Dilly Knox. He was more than a little disappointed to be told that ‘they already knew about it’. Surprisingly, despite this, Welchman was very kind in his criticism of Knox.

The work at B.P. was entirely independent from what was going on within MI8 in London even though, inevitably there was some duplication; not surprisingly, bearing in mind the haphazard nature of MI8 in London. In those early days, before the decryption of messages all that they could do both in London and B.P. was to record all the characteristics in a methodical manner, not knowing where this might lead. Sadly, Chatham, this highly efficient and very secret organisation, had been producing this little-used output for some time. Being indecipherable, the actual messages that they were intercepting and painstakingly recording were useless although the intercept operators did not know this rather the reverse. (Later on more than a million un-deciphered messages – all painstakingly recorded – would be destroyed).

Welchman paid at least one visit to Chatham early on his time at B.P., in fact his first outside visit, after joining B.P. was to Chatham. He immediately made friends with Commander Ellingworth who went on to teach him many things that as he put it, he ‘badly needed to know’. However, Welchman did not give away the fact to Ellingworth that B.P. had a number of decoded messages that had been handed over by the French, proving that it was possible, although he did discuss French intercepts in

general. There are tantalising hints that there was more going on at the Fort than just interception in Welchman’s book. On describing this first visit, he mentions that ‘the traffic analysts at Chatham had other (sadly unspecified) tasks’.

In 1940, the services, mainly the War Office, and not the user of the product, Hut 6 as it would become known, controlled the tasks undertaken by the intercept stations. This was a contentious issue. Around 1940, presumably on Butler’s instructions, Chatham even removed six sets from Enigma cover without notifying or consulting with GC & CS. Hut 6 protested but received little

2 Alfred Dillwyn ‘Dilly’ Knox CMG, was originally a British classics scholar and papyrologist at King’s College, Cambridge and chief codebreaker at B.P.

sympathy from the military and air force authorities who considered it to be something of an Act of Grace on their part even to allow GC & Cs any voice in the allocation of the sets. Hut Six had even had to battle to prevent Enigma coverage being transferred from highly skilled civilian army operators to unskilled RAF operators with potentially disastrous results.3

One thing that we do know is that Ellingworth had the highest of security clearances, having been indoctrinated into the secrets of Enigma by the time he visited B.P.’s Hut 6 early in 1940. Welchman had become ‘deeply suspicious of Colonel Butler’s motives and had watched several small set-ups spring up in London in an effort to expand his control over the W/T traffic and to gain as much intelligence as possible.

Group Captain Blandy, head of the RAF Y Service could not resist joining in the dispute. Although the RAF Y Service had not at this stage started to monitor any Luftwaffe ground to air traffic, he wrote patronisingly that ‘Hut six who had been complaining had not begun to understand the niceties of interception and that their complaints would not have been voiced had they attended a course at Chatham or Cheadle on traffic analysis’ which was possibly true while Enigma had not been broken.

Whilst interception work officially ended at Bridgewoods in March 1941 following on from it being bombed when at least one woman (WRAC) killed. The bulk of the staff moved to Chicksands which was followed by a move to Beaumanor due to the discontentment of the female staff who complained bitterly about the presence of bats in the set rooms at the Priory.

3 The Bletchley Park Codebreakers, Ralph Erskine and Michael Smith (eds.), Bantam Bletchley Press, 2001

A group of senior EWAs (Experimental Wireless Assistants) was unofficially still maintained at the Fort as trainers and they undertook the training of many local schoolboys who were recruited for this secret work. Ellingworth was a churchwarden at St Mary’s Strood where the vicar was the Revd Donald Brand. Ellingworth put Brand to work as a recruiter for young men who were considered suitable for secret war work. Recruitment amongst Boy Scouts was particularly successful. Brand also provided initial accommodation for them whilst they underwent their training as Experimental Wireless Assistants. Training took some three months and involved a daily grind of Morse code tuition. Weekly test were taken and these were administered by Albert Stevens who had been a chief instructor in the Royal Signals. Other instructors, Hadler and Blundell, were from the first five operators recruited as early as 1926.

There was a rather bizarre end to this story. At the end of the war, in 1945, despite the invaluable work that they had done as civilians working in a military capacity, the ‘schoolboys’ would all be conscripted into the Royal Signals to undertake their national service. Most went on to end up working for GCHQ in various capacities and at least one, Sandy Le Gassick, went on to attain the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and was awarded the MBE.

There is no doubt that these operators were probably amongst the finest in the ‘business’. One member of the Fort staff, Chief Petty Officer Albert Stevens RN, is said to have taken a perfect copy of the long signal sent to Group North by Bismarck and it is claimed that it was from this signal that the Admiralty were able to pinpoint the location of Bismarck after initial contact had been lost. This claim should be treated with some caution as there was no D/F facility at the Fort and the Fort was not usually involved in naval traffic. It was shortly after this, though, that Bismarck was sunk by ships of the Home Fleet. A similar claim – probably baseless – is made for Chicksands. The story goes that Stevens was called to see Ellingworth in his office shortly after this event under the impression that he was in for a rollicking for some error, but instead was given a generous measure of whisky and told that he had ‘played a vital part in the sinking of the Bismarck’.

It was during a night watch at Bletchley Park, a year or so later, that Ellingworth introduced Welchman to one of his secrets; the fact that, completely unknown to B.P., he had maintained a core of operators at Bridgwoods after the move to Chicksands (and then Beaumanor). They provided a diversity of interception so what could not be heard at Chicksands or Beaumanor could possibly be intercepted at Fort Bridgewoods. This small force would be maintained until the end of WWII, proving its value.

With Butler eventually out of the way, Welchman established a closer personal relationship with Lieutenant Commander (retd) Ellingworth RN the officer in charge at Bridgewoods, which continued throughout the war particularly after the move to Beaumanor when Ellingworth became in charge of the operators there. This relationship brought about a vital interplay between Hut 6 at Bletchley and the heads of watch at Beaumanor and Bridgewoods Whilst at Bridgewoods, Welchman had talked to Ellingworth about certain messages being given priority. As a result, the message headings, including message disciminants, for certain intercepted priority traffic were sent by teleprinter to Bletchley Park so that messages that were likely to be capable of a break could be transmitted to them as priority. These became known at Bridgewoods as ‘Welchman Specials’. Initially Welchman was concerned at the security implications of his name being used but there was no need for concern. There was another ground for concern in that the operators were under the impression that all the messages that they were painstakingly logging were being decrypted. Would they have been quite so diligent had they known that their work was destined for the wastepaper baskets?

It appears that the Fort was not dedicated entirely to Enigma. There is evidence from ex-members of the staff that interception work at Bridgewoods was also linked directly with the work undertaken by Professor R V Jones and his battle of the beams and the Knickerbein beacons. Bridgewoods was definitely taking German Air Force traffic from the experimental unit that was working on the beam transmitting stations, and thereafter from the beam station organisation some of which was in ‘plain language’ due to the incompetence of the operators. By then, some secrets of Enigma (Red) had been broken and this enabled Prof ‘Bimbo’ Norman in Hut 3 to alert Jones to vital messages that allowed him to ‘break the beams’ as Churchill was to put it.4

MI8 was not only concerned with Enigma also; in fact, Butler and the majority of those concerned initially were of the opinion (correctly) that it was, as a machine cipher, unbreakable. The signals intelligence department of the War Office ran the Y station network. Additionally, for an 18-month period, from late 1939 until mid 1941 it also ran the Radio Security Service, under the designation of MI8c. At the start of WWII, Vernan Kell the head of MI5 had introduced a contingency plan to deal with the problem of illicit radio transmissions. A new body was created, the Radio Security Service (RSS), headed by Major J P G Worlledge. He was not new to the intercept world. Until 1927, Worlledge had commanded a Military Wireless (intercept) Company at Sarafand in Palestine. His brief now was to; intercept, locate and close down illicit wireless stations operated either by enemy agents in Great Britain or by other persons not being licensed to do so under Defence Regulations, 1939’. As a security precaution, RSS was also initially given the cover designation of MI8. Working from cells at Wormwood Scrubs, Worlledge selected Majors Sclater and Cole-Adams as his assistants, and Walter Gill as his chief traffic analyst. Gill had been engaged in wireless interception in World War I and recommended that the best course of action would be to find the transmissions of the agent control stations in Germany. He recruited a research fellow from Oxford, Hugh Trevor Roper, who was fluent in German. Working alongside them, at Wormwood Scrubs, was John Masterman, who later would run MI5’s double-agent XX program. Masterman already had agent SNOW,5 and Gill used his codes as the basis for decrypting incoming agent traffic.

RSS assigned the task of developing a comprehensive listening organisation to Ralph Mansfield, 4th Baron Sandhurst, an enthusiastic amateur radio operator. He had served with the Royal Engineers Signal Service during World War I and had been commissioned as a major in the Royal Corps of Signals in 1939. Sandhurst was given an office in the Security Service’s temporary accommodation in Wormwood Scrubs prison. He began by approaching the president of the Radio Society of Great Britain (RSGB), Arthur Watts. Watts was not new to the Sigint world having served as an analyst in Room 40 during World War I following the loss of a leg at Gallipoli. Watts recommended that for a start, Sandhurst recruit the entire RSGB Council, which he did. The RSGB Council then began to recruit the society’s members as voluntary interceptors (VI). Radio amateurs were considered ideal for such work because they were widely distributed across the UK.

4 Most Secret War, R V Jones, Penguin, 2009, pp. 127

5Arthur Graham Owens, later known as Arthur Graham White (14 April 1899–24 December 1957) was a Welsh double agent for the Allies during the Second World War. He was working for MI5 while appearing to the Abwehr (the German intelligence agency) to be one of their agents. Owens was known to MI5 by the codename SNOW, which was chosen as it is a partial anagram of his last name.

The VIs were mostly working men of non-military age, working in their own time and using their own equipment. Their transmitters had been impounded on the outbreak of war, but their receivers had not. They were ordered to ignore commercial and military traffic and, to concentrate on more elusive transmissions. Each VI was given a minimum number of intercepts to make each month. Reaching that number gave them exemption from other duties, such as fire watching. Many of the VIs were issued a special DR12 identity card. This allowed them to enter premises which they suspected to be the transmission source of unauthorised signals. There is no record of whether these were used. RSS also established a series of radio direction finding stations in the far corners of the British Isles, to identify the locations of the intercepted transmissions.

The recruitment of VIs was slow, since they had to be skilled, discreet, and dedicated. But within three months, 50 VIs were at work and had identified over 600 transmitters – all firmly on the other side of the English Channel. It soon became apparent that there were no enemy agents transmitting from the UK. In fact, all German agents entering the UK were promptly captured and either interned or turned to operate as double agents under the supervision of the XX Committee. In some cases, a British operator took over their transmissions, impersonating them. The German military, it appears, did not realise this. By May 1940, it was clear that RSS’s initial mission to locate enemy agents in the UK was complete.

Initially, messages logged by VIs were sent to Wormwood Scrubs. But, as the volume became great and as Wormwood began to suffer German air attacks, RSS sought larger premises. They chose Arkley View, a large country house near the village of Arkley in the London Borough of Barnet which had already been requisitioned for an intercept station. It was given the cryptic postal address of Box 25, Barnet. There, a staff of Intelligence Corps analysts and cryptographers began their duties. The RSS had in effect become the civilian counterpart of the military’s Y Service intercept network. By mid-1941, up to a staggering 10,000 logs (message sheets) a day were being sent to Arkley and then forwarded to B.P.

Although it was not in their remit, in early 1940, Trevor-Roper and E W B. Gill had the temerity to successfully decrypt some of these intercepts which demonstrated the relevance of the material, but succeeded in annoying both B.P. and MI6 in the process. In May 1941, RSS’s success and this resentment resulted in control of the organisation to be transferred. There was brief battle over who should control it but, in the end, it became the communication and interception service of MI6. Prior to this they had no such dedicated capability. From this, Trevor-Roper formed a low opinion, which he later expressed, of most pre-war professional intelligence agents.

The new controller of RSS was Lieutenant Colonel E F Maltby and from 1942, Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth Morton Evans was appointed Deputy Controller. Roland Keen, author of Wireless Direction Finding, was the officer-in-charge of engineering. By now, the service was well financed and equipped with a new central radio station at Hanslope Park in Buckinghamshire (designated Special Communications Unit No.3 or SCU3). The Abwehr was now being monitored around the clock. The volume and regularity of the obtained material, enabled Bletchley to achieve one of its great triumphs in December 1941, when it broke the Abwehr’s Enigma cypher, giving enormous insight into German intelligence operations.

At its peak from 1943 to 1944, RSS employed – apart from VIs – more than 1,500 personnel most of whom had been amateur radio operators. Over half of these worked as interceptors while a number investigated the numerous enemy radio networks. This revealed important information, even when it was not possible to decode messages. Few transmissions by secret agents of German Intelligence were believed to have evaded RSS’s notice. Changes in procedure, which the Germans used for security, were in many cases identified before the enemy had become familiar with them. Following the end of the war, RSS HQ moved to Eastcote and was absorbed by GC & CS, by then GCHQ.

One only has to mention Bletchley Park and inevitably you will get the response, Enigma. Bearing in mind how much of Enigma was unreadable for much of the early days of the war it is somewhat surprising that other methods of extracting intelligence and their product, have in the main been ignored or overlooked. These methods other than by decryption, have, over the 60-odd years since the end of the war, received far less attention than the actual breaking of Enigma and its product – decrypted messages. Probably with the tacit approval of the authorities, possibly a deliberate ploy to help maintain the story that operated properly, Enigma was unbreakable?

One aspect of Enigma we do know of is that much of the material that R V Jones had to support his beating the beams battle was derived from German high-grade Enigma traffic, probably intercepted at the Fort. In his memoirs, Professor Jones mentions the fact that he was a regular and welcome visitor to B.P. and was a close friend of Winterbotham, (possibly due to the senior RAF position he held within MI6) but unfortunately, nowhere in his book Most Secret War: The Story of British Scientific Intelligence 1939-1945 does he reveal anything of the co-operation with Bridgewoods; though, interestingly, he makes several mentions of ‘the contributions made by the RAF Intercept Stations’. Could Jones have been confused or misled, one wonders, about the origins of the information? But is this likely although Chicksands with its male operators did not open until 1941; almost a year after ‘Freya’?6 The beam traffic was quite remarkable, as Bridgewoods had managed to find the radio traffic of the German experimental unit that was developing the beam stations and beam flying. These were not well-trained radio operators but scientists and consequently they innocently betrayed their radio frequency schedules and Enigma settings. On one particular day, one of the operators at Bridgewoods took traffic in plain language from this group who were trying to sort out an Enigma setting problem, and during the course of the exchange [all in Morse code] they gave the wheel setting and plug settings on the Enigma machine on that day, a godsend to Bletchley!

At B.P. before Enigma was broken, what little intelligence that could be obtained apart from direction finding came from the analysis of what were known as the preambles of what, by then, had been recognised as Enigma messages. Unknown to them, coincidentally, similar work as going on within MI8 in London. Initially formed on May 16 1918, MI8’s role at that time was the censorship of telegraphic cable traffic. Conveniently it was housed in Electra House, London, home of the Eastern Telegraph Company, (later to be merged into Cable & Wireless). It had a very short post-war life as it was abolished in 1919 as part of the post-war reorganisations. A few days after the outbreak of war in September 1939, an offshoot of MI1(X), was formed, called Military Intelligence Branch 8 (MI8).7 Its role was to ‘collate and pass on to the proper quarters intelligence derived from study of enemy communication systems and to recruit and administer the military personnel needed for signal intelligence’. It was given responsibility for all the army intercept stations, the so-called ‘Y Service’ in

6 One of the first to give British Intelligence any details about the Freya radar was a young Danish flight lieutenant. Thomas Sneum who at great risk to his life, photographed the radar installation on the Danish island of Fano in 1941, bringing the negatives to Britain in a dramatic flight

7 (WO165/38)

the UK. It was placed under the command of the newly promoted Colonel Arcedeckne-Butler who, from 1934 up until then, had been scientific officer and superintendent of a unit known as Signals Experimental Establishment at Woolwich in London, where they were developing radio equipment for the army. It included early work on what came to be known as radar. It would appear that he rapidly gained the view that developing traffic analysis could provide valuable intelligence. MI8 would be the channel through which Sigint would pass to the branches doing substantive intelligence and would also become the centre for all army traffic analysis. In this organisation a small group of analysts was beginning to study the German radio networks which could be constructed from the Chatham intercept reports. Their objectives were very different from Welchman’s. Whilst he was still concerned with their hopes for breaking Enigma traffic, they, MI8 had started with the assumption that the Enigma traffic was unbreakable. Their objective instead was to derive intelligence from a detailed study of these radio nets.

The Enigma messages as transmitted by the German operator would consist of what appeared to be an unenciphered preamble followed by an enciphered text. The preamble was quickly established as being part of the procedure for encoding and decoding the encrypted part of the text. A typical message contained six potentially valuable items of information

The callsigns of the radio stations involved: first the sending station then the destination(s). The time of origin of the message

The number of letters in the text (in five-figure groups)

An indication of whether the message was complete or was a specified part of a multi-part message

A three-letter group which Welchman and Kendrick called the discriminant which enabled the different types of Enigma traffic to be recognised; and

A second three- letter group which became known as the indicator setting.

This would all be followed by the operator making a note of the time of the transmission and the frequency on which it had been transmitted.

At its simplest, T/A, as it is usually referred to, is the investigation and analysis of wireless networks, who is involved in them, the examination and analysis of operating frequencies, callsigns and operator chat in what is generally referred to as plain language. Without this who is saying what and to whom, the efforts of Bletchley Park would have been wasted as a source of intelligence. As a measure perhaps of its importance to the intelligence world the official history, a B.P., department known as SIXTA, with its appendices, is one of the most important components of T/A during the war – has still not (as at 2016) been released.

There was certainly an MI8 presence as can be seen in the photograph of the Fort’s Home Guard There in the front row is Captain (later Major) Jolowicz of the Intelligence Corps who would also work in No.6 I.S. This was the first – possibly the only – indication of any Corps members being based at Chatham. It is interesting that he is wearing the Corps cap badge very soon after the founding of the Corps, having been transferred as temporary captain from the General List to the Intelligence Corps. He was one of the key people working in the Compilation and Records Room (CRR) z. He was later employed in the No. 6 Intelligence School, formed on 25 March 1941, which was known, firstly, as Intelligence School VI and then as Intelligence School No. 6. This school was possibly the source of the controversy between Welchman and Butler. Lieutenant Colonel Thompson opened the headquarters of No. 6 I.S (6I.S) His instructions were to ‘concentrate on research into German methods of signals and wireless procedure’ at Beaumanor, known as War Office Y Group. In July 1941. Its role was redefined as ‘to teach and carry out analysis of the enemy signals traffic (in other words, traffic analysis), building up a picture of the enemy’s communications’. On 1 August, the school was formally opened ‘to control WOYG (War Office Y Group). From here, the original Fusion Room would operate. Later, it moved to 57 Netherhall Gardens Hampstead in 1943 under Colonel Lithgow with Major Jolowicz, a member of the staff, his own house becoming the officers’ mess. The name of the unit was changed to Special W/T Training and Research Wing. Courses would last about six weeks and were mixed courses for intelligence officers and NCOs of the British and Canadian armies who were to staff S.W. Sections for the invasion of Western Europe. Following the move from Beaumanor, No. 6 Intelligence School Merged into B.P. and would later become part of what became known as Sixta. Jolowycz went with them to be employed in the military wing.

To go back to the photo for a moment; next to Jolowycz is a ‘Capt Owen (CRR). We know that there was a Captain W.J Owen who was in the Corps and who is known, like Jolowycz, to have worked in the Mil Wing of GC&CS. CRR (Compilation & Records Room) was of course the department in which Jolowycz was employed whilst at the Fort.

Bridgewoods had played a pivotal part in the initial Enigma breaks, as the quality of the interception was so good. Indeed some of the B.P. codebreakers wrote to Churchill, complaining, when they found that Bridgewoods was to be closed and the service moved to Chicksands where the operators were notoriously slipshod and then, even worse, to the unknown Beaumanor. The move to Chicksands was almost certainly precipitated by a bombing incident in October 1940 when a stray oil bomb made a direct hit on the bridge over the moat where several vehicles were parked at the changeover of the shift. Several people were killed, including three ATS teleprinter operators. A Sub Lieutenant Connely RNVR dived for cover under one of the vehicles and fortunately chose the one that was not directly hit! Sidney Wort, later Major Wort, and second-in-command to Ellingworth had to attend the mortuary the following day and identify the bodies.

It is a shame that Bridgewoods did not survive in the same way that Bletchley Park has and, until now, has not been given the credit for the vital work that was done there. Whilst the story of Enigma has become part of the national history, the work of the interception stations is still shrouded in secrecy as in 1945, they did not stop but merely changing their focus to the ‘Bear in the East’. Efforts were made to introduce the monitoring of French traffic but this disloyalty caused such anger amongst B.P. staff that the idea had to be dropped!

In 1953 Ellingworth retired from Beaumanor, then an intercept station and training centre for operators outside of Leicester, he received an OBE for his war work. The schoolboys were all posted into the Royal Signals in 1945 to undertake their national service. Most ended up working for GCHQ in various capacities and at least one, Sandy Le Gassic, went on to attain the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and was awarded the MBE. The search for No. 1 Intelligence School goes on.

I was sitting, thinking as I do about various Sigint puzzles when suddenly a thought came to mind. B.P. as GC&CS described it as a ‘School’. Was it possible that it had been known at some time as ‘No. 1’?

If so, I need not look any further

The Hut Six Story, W G Welchman, McGraw Hill, 1984

The Bletchley Park Codebreakers, Ralph Erskine and Michael Smith (eds.), Bantam Press, 2001 Pursuit: The Sinking of the Bismarck, Ludovic Kennedy, Fontana, 2001.

Most Secret War: The Story of British Scientific Intelligence 1939-1945, R V Jones, Penguin, 2009 Wireless Direction Finding, Roland Keen, Illife & Sons, 1938.